Tibetan Mandalas: Are they really what you think they are?

Encountering Tibetan Art

In the late 1990’s my Mom and I visited the Tibetan Buddhist art collection within the Asian Art Museum in San Francisco. Mom was a minister of Spiritual Science and a voracious reader of all the mystery traditions of the world. There were, seemingly, no great mystics of the 1970’s and 80’s who she had not encountered, from Ram Dass to the Dalai Lama and the Karmapa. She had traveled to India and Nepal and the stupa complex at Borobudur, Indonesia. She was also a great art appreciator, from her college days where she majored in Art History, to her years of scouring every gallery at the Smithsonian near our home in Washington, perusing every visiting collection, including the Sackler and Freer Galleries that display fine examples of Himalayan scroll paintings (thanka) depicting a traditional deity mandalas. But her comments made me realize something shocking: My mother had no idea what the purpose of the deity mandala we were looking at was.

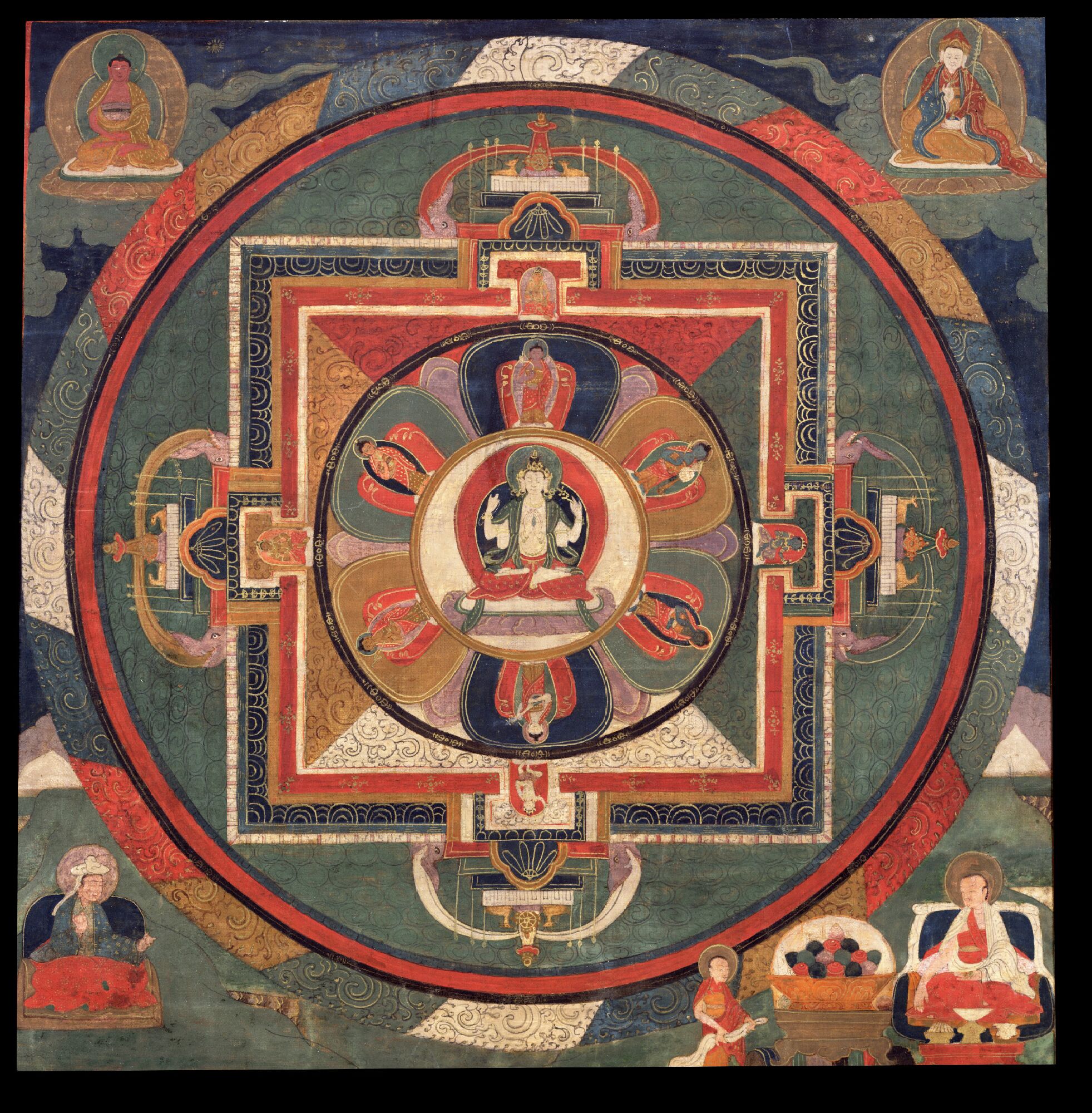

Now, I’m not an expert. Certainly, mandalas represent many different things, even within Vajrayana (Buddhist tantra). But when you see a deity, or the symbol of one, in the center of a traditional painted mandala it serves as a blueprint. On the one hand, there are mandalas that represent the universe as it was perceived in ancient India, typically featuring a towering Mount Meru in the center and seven seas and subcontinents surrounding it. But most traditional painted mandalas do not represent this.

Wisdom Deity

Let’s back up a bit. Part of every initiated Vajrayana practitioners’ life is shifting one’s sense of identity from being the person named such-and-such, born from our mother’s womb, made of flesh and blood, and having a human story-line and personality, to wisdom deity born from a lotus made of colorful light and abiding timelessly.

Now, here’s where the deity mandala comes in. As we engage in self-visualization as a light deity as a practice, both on and off the cushion, we see our environment, the pure aspect of the elements that make up the universe, as mandala. One’s own awareness is at the center, surrounded by various ancillary deities arrayed around us who represent various aspects of awakened mind and enlightened activity. This is all described in a specific section of a recited practice text called the “lha kye,” the birth of the deity. There may be commentaries by revered masters that supply still more details, such as how to do the practice, and the specific symbolism used. It is all quite precise and comes down to us from ancient India one way or another. The deities are usually enclosed in a palace, our house, with a specific shape, color, and ornaments. Out beyond the palace’s walls, the outer boundary of one’s “universe” is enclosed in a protective dome.

Blueprint of Your Reality

Mandala paintings are primarily an aid to practitioners of this style of practice, after they have forged a relationship with an enlightened master, received empowerment to do the practice via a ceremony, been given oral transmission of the practice text, and taught how to do it. Like a blueprint, the viewer looks into a cut-away view of the palace from above.

Like peeping from a helicopter at the remains of a house whose roof has been torn off by a tornado, looking at a painting of an unfamiliar deity mandala in a gallery or on the internet gives me the feeling of spying into someone else’s home I can’t stop looking, but it’s a bit T.M.I. The experience of being the deity and experiencing the world as our mandala is an intimate one.

Mom, wherever your mindstream is dwelling since your death in 2007, I hope your exposure to the magnificent art of this powerful practice tradition has drawn you close to an excellent teacher.